Intro

In this one, I want to have a little talk about economics and video games. But don’t worry – it won’t be nearly as tedious as it sounds. The traditional well-dressed, spectacled and slightly booring academic economist likes to neatly categorize the world he sees. Preferably, he wants to find a way to fit it into a finite equation that can then be analyzed until the whole class is asleep. Funnily enough, video games don’t fit his precious framework all that well.

The goal of this article is therefore figuring out what kind of economic good is a video game and how do we go about making sense of the industry? In the process, we will talk a little bit about the existing theory of goods and then look at the unanswered questions that video games bring to the table.

Goods, goods, goods

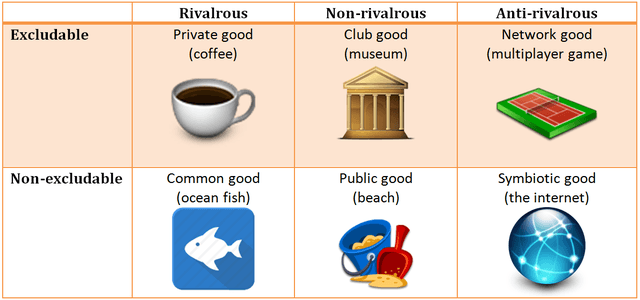

You see, a video game is a good – just like an ice cream or a city park – video games serve benefit to the people who consume them. So how do we characterize goods? Well, the usual way is to look at two different aspects. Firstly, we ask whether a good is excludable – can the seller/owner of the good restrict the amount of consumers consuming it? For an ice cream its cheap and easy to make sure only the guy buying the ice cream gets to consume it. For a city park – not so much.

The second question deals with rivalry – is the amount of benefit a consumer receives reduced, if more than one person consumes the good? Rival goods are then those, which decrease in value if more than one person consumes them at the same time. A good example are the fish in the ocean – if everyone goes fishing, we are all individually worse off, than if only one of us gets to fish, cause we are likely to overfish in the long term. Non-rival goods are those for which there is no reduction in benefit, up to a certain level of congestion (you might say fishing is non-rivalrous up to an extent).

If you fit the picture together, you get something like this.

So where do video games fit in the traditional framework? Well, a standard video game is certainly excludable (free-to-play just has a price of zero), and it is definitely not rivalrous. Note that this is meant in the sense that you can’t exhaust the copies available and up to a certain level of congestion, no consumer is worse off because of others joining the community. But are they like a city park or a beach? Are you just indifferent of other people playing or are you actually better off having more people involved in the community?

For a multiplayer game, you certainly prefer having some playmates, but it partially applies to other games as well – a player likes to have access to more reviews, more guides and tips, more mods, more servers, more clans and more of the developers love (congestion to consider), rather than be one of the select few playing a game that even the developers have turned their back on (Rust Legacy sob…).

The more the merrier – network effect

Way back in 1908, people in the Bell Telephone company started talking about network effects – the notion of telecommunication consumers being better off, if more people engage in using the product. Some noteworthy academic work on this can be traced in the 80’s and 90’s, however the most comprehensive research was done after the popularization of the internet, as the definition nicely fit software, social networks and many other virtual goods.

In 2004 Steven Weber, a professor at the University of California, coined a new category of goods – anti-rival goods. He specifically referred to goods, that increase in value, as more people consume them, mentioning network effect as the most popular cause. Now, technically non-rival goods have a “non-negative” change in consumption value, as more people consume them, so according to the definition anti-rival goods fit in that category. However, times are changing and observations of network effects are becoming more and more frequent, so something has to give.

Goods, goods, games

With this in mind, let’s modify the traditional economists table a bit, shall we?

The greatest benefit to society is surely raised from Symbiotic goods, such as the internet – for most access is unrestricted or even free and the more people use it, the better everyone is. Most video games are then anti-rivalrous and excludable – network goods. As such, the benefit they serve increases as more people engage in consumption, however the owners can still restrict people from consumption. This then tells us that the more people already play a given game, the more potential benefit is perceived by new consumers and, the higher the willingness to pay.

Ideas for developing further understanding

The concept of network goods and the notion of network effects opens up a variety of questions to investigate and video games are the perfect place to do the studies.

Questions worth considering include

#1 Is there any relation between the prices people are willing to pay for games and active player count/existing copies sold? (articles here and here)

#2 Are there developers, who try to engage in excessive profiteering at the expense of consumer surplus, as people are eager to join their communities?

#3 What benefits does the popularity of free-to-play games bring the community (Steam for example) and how does the consumption of complementary goods (in-game items/upgrades etc.) change, as more people engage in playing a free-to-play game?

#4 How does competition work in the gaming industry – an industry where the large developers have a competitive advantage, while small ones are struggling to attract a sufficient user base?

#5 How are consumers distributed in this “large-firms-easily-get-larger” industry? (article here)

Outro

I think you will agree, we have achieved a little bit of understanding and some kind of conceptual framework for thinking about video games and the economics of the game industry. Now, the traditional economist has some cool concepts and useful methods in his tool belt. However, as we can see, video games have some characteristics science has started to properly study only in recent years, not to mention they open up a whole can of worms in terms of unanswered questions. I hope you find this as inspiring as I do – every minute of your gaming gives humanity more reason to be curious and gain more understanding of itself.

So, keep on gaming in the free world!

Published: Oct 3, 2015 08:12 am